The Dirties is one of my favorite films of the year, an exceptionally timed black comedy about a lonely, movie-obsessed boy getting lost in the project whose vicarious revenge against his bullies tips ever more precipitously into a literal quest for vengeance. Matt Johnson, director, co-writer and star, captures with uncomfortable accuracy the young man who can communicate only in obvious and obscure references, and who gets so fixated on the one thing that gives him solace that it becomes an escape from reality that threatens to horribly alter that reality. Yet it remains funny, Johnson's pubescent cherub face an open book as he naïvely carries on, deluded with flashes of self-awareness. And in the end, where his decisions start to become less about his rational, human choices than a slavish devotion to the narrative arc of his movie, that grim humor becomes fully tragic.

Read my full review at Spectrum Culture.

Personal blog of freelance critic Jake Cole, with exclusive content and links to writing around the Web.

Monday, October 28, 2013

Thursday, October 24, 2013

Leviathan (Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Verena Paravel, 2013)

I've been dying to see this film for nearly a year and a half, and I'm thrilled to say that Leviathan more than lives up to its reputation as very possibly the greatest and most singular cinematic achievement of the decade so far. My review scrambles for a few literary and filmic touchstones just to process it, but this film feels so unlike anything I've seen, even other works by the Harvard Sensory Ethnography Lab. I cannot recommend it enough, and even though I lack a reference to the film's theatrical impact, I can safely say that Cinema Guild's Blu-Ray gets the job done.

Check out my review of the film and its home-video release at Slant.

Check out my review of the film and its home-video release at Slant.

Wednesday, October 23, 2013

Pauline Kael—5001 Nights at the Movies

There's been a resurgence in publication of Pauline Kael's work in the last few years after a 2011 mini-renaissance that saw some biographies and a new collection issued. It's long overdue, though part of the frustration of having to clamor together Kael's pieces around the Internet when most of her work was OOP is realizing how narrow your concept of her really was. Case in point, I was so used to digging out her more famous and easily available long-form pieces that I had no exposure to her capsule writing. This collection, then, was a bit of a surprise once I cracked it open, and honestly a bit of a disappointment. I'm enraptured when Kael gets going, even when I disagree, but this format doesn't allow her to build an argument, so that each dismissal has a nasty curtness to it. I admit a bias in that I think most capsules read this way (including mine), and that I can count on one hand the critics who seem to make an art of it (Agee and Fernando Croce) being the best. Still, it's good to have a fuller portrait of Kael's work, even if this aspect of it does not thrill me at all like her essays.

Read my full review at Spectrum Culture.

Read my full review at Spectrum Culture.

Tuesday, October 22, 2013

The Smashing Pumpkins—Siamese Dream

I was never into the Smashing Pumpkins growing up, but a recent relisten to their catalog has been revelatory. Of them, Siamese Dream is obviously the crowning achievement, a work that splits the difference between early-'90s alternative vagueness and experimentation and classic rock ambition and results in something patently calculated yet undeniably compelling. It's made to be listened to over and over, but at least Billy Corgan did us the solid of making it more than worth the time.

My retrospective review is up at Spectrum Culture.

My retrospective review is up at Spectrum Culture.

I Declare War (Jason Lapeyre and Robert Wilson, 2013)

Meaningless display of young machismo that mistakes depiction of extremity as commentary. A waste of time. Read my full review at Spectrum Culture.

24 Hour Party People (Michael Winterbottom, 2002)

Post-punk is my favorite genre of music (one of these days, I must get back to my series of posts on The Fall, possibly my favorite band), and Michael Winterbottom's glibly self-referential, knowingly material work is not only the greatest possible snapshot of that freewheeling mini-era of music in the wake of punk's return to zero, but maybe the single best evocation of a musically defined time period put to film. Hilariously funny, the film's put-upon, sad-sack nature fits its subject well, not only quixotic Factory Records head Tony Wilson but the broader post-punk movement, which infiltrated pop charts with subversively catchy rhythms before becoming simply the new pop, period, intellectual exercises ultimately hoisted on their own petard. There's something grimly amusing about the film being at its brightest when misery purveyors Joy Division start to gain traction and at its lowest when ecstasy hits the clubs, but that's the contradictory, witty way of the film in a nutshell.

Read my full review at Spectrum Culture.

Read my full review at Spectrum Culture.

Monday, October 21, 2013

In Search of Blind Joe Death: The Saga of John Fahey (James Cullingham, 2013)

John Fahey is one of the best and most overlooked guitarists of the 20th century, and James Cullingham's mini-feature does about as good a job as one can do in bringing the recluse to life. Fahey left little in the way of anecdotal or personal value, which leaves little for the director to sink his teeth into. But then, Fahey left behind a considerable back catalogue of avant-garde but eminently listenable music, a nexus point of Eastern classical and Memphis blues that found constant variation in repetitious structures. Cullingham is at his best when he finds ways to visually ape those compositions, but in all this is one of those documentaries that succeeds artistically only in the sense it makes you want to see out the subject's work.

My full review is up at Spectrum Culture.

My full review is up at Spectrum Culture.

Talking Mystery Train with Allison Kupatt

I loved Jim Jarmusch's latest, Only Lovers Left Alive, so much when I saw it at TIFF that I was eager to revisit some of the director's other work and talk about it, particularly the films that reminded me most of Only Lovers, Down By Law and Mystery Train. I had a back-and-forth discussion with Allion Kupatt of Nerdvampire about the latter, a transcript of which has been reproduced below. I had a great time talking to Allison about the film, which is one of the Jarmusch films I love best but the one I've had the hardest time articulating what it is about the movie that grabs me. Having a companion to discuss it was a great pleasure, not only to hear what someone else took from this intimate movie but to help clarify my own long-clouded thoughts. Anyway, if you haven't seen Mystery Train, I highly recommend it (you can watch it on Criterion's Hulu+ channel, which is the best $8/month you can possibly spend). If you have, check out our breakdown, after the jump.

Sunday, October 20, 2013

The Canyons (Paul Schrader, 2013)

I neither think of The Canyons as a maligned film maudit nor a justified one. Instead, it is a film whose flaws are readily apparent but also, on occasion, the thing that makes the film so fascinating. It's hard to watch Lohan in this, not just for the times in which it looks as if she definitively wasted her potential but for the fleeting moments in which she shows she still has something to give. In all likelihood, the work is her Wrestler, a role so specifically calibrated around her downfall that she could never match it again, nor could any role offer the chance. Now, she's no Mickey Rourke, and this movie's no Wrestler (though it's tawdry, ramshackle nature reveals itself to be the level on which Bret Easton Ellis' coke-dusted nonsense should operate, instead of shinier, higher rises), but if Lohan doesn't get at least some boost from this—and she won't—part of the reason is encoded into this movie and its caustic look at an industry that sets upon anyone who dares to stop pretending that it is all good times.

My full review is up at Spectrum Culture.

My full review is up at Spectrum Culture.

Stranded (Roger Christian, 2013)

Poor Roger Christian, director of Battlefield Earth: who else could have a film this bad and it not be the worst of his career by a long shot? Another belated link, check out my review at Spectrum Culture.

Camille Claudel, 1915 (Bruno Dumont, 2013)

This was my first Bruno Dumont film, and I've heard it's something of a departure for casting so prominent a star as Juliette Binoche. On the evidence of this film, though, I'm not exactly rushing out to catch up on his filmography. Nakedly exploitative, the film relies on a cast of actual mental patients to hammer home the point that Binoche's sculptor does not belong in an asylum, lending the numerous close-ups of blank smiles or pained facial contortions a grotesque element that draws no humanity from their faces. Elsewhere, the blandly ascetic frames, suggesting no inner life, only the starkness of external patriarchy weighing down on the artist, suggest Bresson by way of someone who hasn't paid much attention to Bresson, and for all the didactic fuss the film attempts to make about Claudel's outrageous silencing, the camera itself only ever takes the point of view of the men.

My full review is up now at Spectrum Culture.

My full review is up now at Spectrum Culture.

Halloween II (Rob Zombie, 2009)

Originally published at the now defunct Cinespect.

Rob Zombie’s 2007 “Halloween” remake loosely applied the director’s quickly coalescing tics to the John Carpenter-directed original, recasting the blank, seemingly motivationless killer Michael Myers as a hollowed-out hick with family issues and eyes that looked as if they’d taken on a paint-huffing-induced glaze while still in utero. Yet the film, Zombie’s open concession to mainstream genre demands, while cementing his style, left cracks in it. Those minuscule fissures are blown open by “Halloween II” (2009), an ostensible cash-grab that proved, especially in its slightly but meaningfully altered director’s cut, the best horror film of the last five years.

The sequel continues the story along a path that seems logical until one realizes how few horror franchises do it, caring less for the further exploits of monsters and their victims than for the aftershocks of the original trauma. “Halloween II” presents a group of characters irrevocably poisoned by their brush with evil, among them Dr. Loomis (Malcolm McDowell), who is hawking a book to profit off his ghastly failure to cure—or even contain—Michael’s psychosis, and Michael’s sister, Laurie (Scout Taylor-Compton), who is in total emotional freefall.

Laurie’s situation establishes the film’s focus as one in which the monster is as much post-traumatic stress disorder as it is Michael Myers. Taylor-Compton is no great shakes as an actress, but she gives what may be the most Cassavetian performance to ever grace a horror film. It’s an unvarnished, all-consuming portrait of madness that makes it difficult to sympathize with Laurie, especially when her caustic emotional pain is juxtaposed with the more visible scars adorning her friend Annie, who tries to handle her own trauma with more poise.

So pervasively does Taylor-Compton yoke the film into her character’s warped soul that one could argue that Michael Myers never truly returns in this film, and that his subsequent rampage is but a product of her mind. Various dream sequences offer some support for that notion, though buried amid Laurie’s own anxieties of genetically inherited and trauma-induced mania are explicit critiques of the Oedipal and misogynistic traits that the character of Michael Myers set loose upon the slasher genre, which the original “Halloween” (1978) helped establish 35 years ago.

The nightmares break up Zombie’s style, which was previously marked by a use of medium and long shots to capture action. The camera frequently presses in close on Taylor-Compton’s face, but not without a hint of resistance that suggests it wishes it could pull away.

Other aspects of Zombie’s aesthetic change as he shakes the cornmeal breading off his demented carnival look, adopting a more dreamlike state that can be seen fully realized in his latest film, “The Lords of Salem” (2012). His humid imagery gives way to an autumnal chill, light flickering through cool blue air as demons inevitably begin to stalk Laurie and those around her. And the deliberation of Michael’s slashes—pneumatic extensions of the elbow that send the knife down with mechanical simplicity—bring brute poetry back to a genre that arguably had not enjoyed it since the first time Michael Myers invaded the screen.

Rob Zombie’s 2007 “Halloween” remake loosely applied the director’s quickly coalescing tics to the John Carpenter-directed original, recasting the blank, seemingly motivationless killer Michael Myers as a hollowed-out hick with family issues and eyes that looked as if they’d taken on a paint-huffing-induced glaze while still in utero. Yet the film, Zombie’s open concession to mainstream genre demands, while cementing his style, left cracks in it. Those minuscule fissures are blown open by “Halloween II” (2009), an ostensible cash-grab that proved, especially in its slightly but meaningfully altered director’s cut, the best horror film of the last five years.

The sequel continues the story along a path that seems logical until one realizes how few horror franchises do it, caring less for the further exploits of monsters and their victims than for the aftershocks of the original trauma. “Halloween II” presents a group of characters irrevocably poisoned by their brush with evil, among them Dr. Loomis (Malcolm McDowell), who is hawking a book to profit off his ghastly failure to cure—or even contain—Michael’s psychosis, and Michael’s sister, Laurie (Scout Taylor-Compton), who is in total emotional freefall.

Laurie’s situation establishes the film’s focus as one in which the monster is as much post-traumatic stress disorder as it is Michael Myers. Taylor-Compton is no great shakes as an actress, but she gives what may be the most Cassavetian performance to ever grace a horror film. It’s an unvarnished, all-consuming portrait of madness that makes it difficult to sympathize with Laurie, especially when her caustic emotional pain is juxtaposed with the more visible scars adorning her friend Annie, who tries to handle her own trauma with more poise.

So pervasively does Taylor-Compton yoke the film into her character’s warped soul that one could argue that Michael Myers never truly returns in this film, and that his subsequent rampage is but a product of her mind. Various dream sequences offer some support for that notion, though buried amid Laurie’s own anxieties of genetically inherited and trauma-induced mania are explicit critiques of the Oedipal and misogynistic traits that the character of Michael Myers set loose upon the slasher genre, which the original “Halloween” (1978) helped establish 35 years ago.

The nightmares break up Zombie’s style, which was previously marked by a use of medium and long shots to capture action. The camera frequently presses in close on Taylor-Compton’s face, but not without a hint of resistance that suggests it wishes it could pull away.

Other aspects of Zombie’s aesthetic change as he shakes the cornmeal breading off his demented carnival look, adopting a more dreamlike state that can be seen fully realized in his latest film, “The Lords of Salem” (2012). His humid imagery gives way to an autumnal chill, light flickering through cool blue air as demons inevitably begin to stalk Laurie and those around her. And the deliberation of Michael’s slashes—pneumatic extensions of the elbow that send the knife down with mechanical simplicity—bring brute poetry back to a genre that arguably had not enjoyed it since the first time Michael Myers invaded the screen.

Friday, October 18, 2013

Metallica: Through the Never (Nimród Antal, 2013)

I've long outgrown my metal phase, but I still love to listen to Metallica. Even so, I never expected to like Through the Never as much as I did. Antal wisely does not chase that rabbit of replicating the concert experience (impossible when cameras reside on-stage), but the film actually does end up putting forward a vision of both the material reality of putting on a Metallica show, and the subjective interplay between the band and the reaction their music prompts. In other words, it's almost the film Godard wanted Sympathy for the Devil to be, albeit with a half-assed approached to politics that thrillingly fades away into the simpler pleasures of getting your skull pounded out by riffs.

My full review is up at Movie Mezzanine.

My full review is up at Movie Mezzanine.

Enough Said (Nicole Holofcener, 2013)

Belatedly linking to last week's review of the fine, sometimes beautiful Enough Said, which sports two incredible lead performance that are so good that the film hits a wall whenever the two main actors aren't both on-screen feeding off each other. In particular, it is hard to see Gandolfini, as he did in Not Fade Away, truly move away from Tony Soprano, and to know that we will never get to see the full development of this next stage of his career. But at least there's this performance, and at least Julia Louis-Dreyfus continues to enjoy a renaissance of her own. So many ancillary elements of the film weigh it down, but these two are alchemical.

Read my full review at Movie Mezzanine.

Read my full review at Movie Mezzanine.

Warner Archive Instants Picks of the Week (10/11/13—10/17/13)

The next Warner Archive picks. This time I'm joined by Ty Landis, who provides his own pick. Read 'em both here.

Thursday, October 17, 2013

Warner Archive Instant Picks (10/4/13—10/10/13)

My first round of Warner Archive picks. Read 'em here.

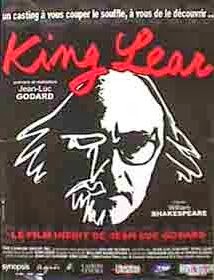

King Lear (Jean-Luc Godard, 1987)

My Godard posts have all been first impressions, for better and worse (especially worse during my early attempts to grapple with him), but I had to watch King Lear three times before I felt comfortable writing about it in any capacity. Possibly Godard's densest work, at least to that point, it is also my favorite of his, an enervating, funny, autocritical and far-reaching work that castigates the artist for his pretentious ambition even as it defends his self-annihilating desire to make cinema all he thinks it can be. Crying out for a proper home video release; maybe Olive Films, who have presented some crucial later Godards already, will pick up the slack.

Read my full review at Spectrum Culture.

Read my full review at Spectrum Culture.

TIFF Capsules

Here are links to the capsules I wrote for Movie Mezzanine during TIFF.

This link contains capsules for Bastards (Claire Denis), Only Lovers Left Alive (Jim Jarmusch) and La última película (Raya Martin and Mark Peranson).

This one talks about Horns (Alexandre Aja) and 'Til Madness Do Us Part (Wang Bing).

This link features capsules for A Spell to Ward Off the Darkness (Ben Rivers and Ben Russell) and Night Moves (Kelly Reichardt).

Also, here are Dork Shelf capsules for Closed Curtain (Jafar Panahi and Kambuzia Partov), A Field in England (Ben Wheatley) and Manakamana (Stephanie Spray and Pacho Velez).

This link contains capsules for Bastards (Claire Denis), Only Lovers Left Alive (Jim Jarmusch) and La última película (Raya Martin and Mark Peranson).

This one talks about Horns (Alexandre Aja) and 'Til Madness Do Us Part (Wang Bing).

This link features capsules for A Spell to Ward Off the Darkness (Ben Rivers and Ben Russell) and Night Moves (Kelly Reichardt).

Also, here are Dork Shelf capsules for Closed Curtain (Jafar Panahi and Kambuzia Partov), A Field in England (Ben Wheatley) and Manakamana (Stephanie Spray and Pacho Velez).

Labels:

2013,

Alexandre Aja,

Claire Denis,

Dork Shelf,

Jim Jarmusch,

Kelly Reichardt,

Movie Mezzanine,

TIFF13,

Wang Bing

Blu-Ray Review: The Big Parade (Warner)

Warner outdid themselves with this nearly flawless transfer of King Vidor's amazing The Big Parade. Barring some inevitable dropped frames and a scant amount of irreparable print damage, I've never seen a silent film look this blemish-free, and if it weren't for the healthy grain I'd assume they'd gone overboard with digital touch-ups. The film itself overwhelmed me, a foundational war film that outdoes nearly all the movies that followed in its wake and shamelessly cribbed its elements. A work of great, ambivalent humanism, rarely castigating patriotic fervor even as it stares honestly at its consequences.

My full review is up at Slant.

My full review is up at Slant.

Wednesday, October 16, 2013

TIFF Review: Gravity

My other post makes my feelings more plain, as this was a quickly written mini-review, but these were my first thoughts on the disappointing Gravity. Read them at Movie Mezzanine.

TIFF Review: Stray Dogs

I don't know when this will get distribution, but for now it is safely my favorite film of 2013, and, if it comes out next year, an extremely high bar for 2014's slate. If this is Tsai Ming-liang's last film, he leaves cinema richer, more evocative and, with his startling use of digital as an extremity of length over assembly, more advanced than he found it. His mostly static takes, stretching for minutes at a time, elicit gulfs of Kuleshov-esque interpretation from actors' subtly modulating faces, playing out a commentary of economic strife, existential isolation and emotional longing with few words. It was the last film I saw in Toronto, and the that best proved that cinema still has new territories to explore.

Read my full review at Film.com.

Read my full review at Film.com.

Anti-Gravity: Why Alfonso Cuarón’s Space Odyssey Is Shortsighted About Long-Takes

So, I was one of a precious few people who found Gravity to be a mediocre film, not just in its weak script (which has been noted even by admirers) but in its meaningless, programmed long-takes. CGI and digital cameras have unlocked new possibilities for extended shots, but I find them to be so hollow, and I place Gravity among films like Episode III and The Avengers that use massively scaled, digitally rendered long-takes that highlight to me only their falsity and the unimpressive accomplishment of adding a shot's mise-en-scène during post-production.

My full essay is up at Film.com.

My full essay is up at Film.com.

Blu-Ray Review: Prince of Darkness (Shout!)

I cannot recommend the new Blu-Ray of Prince of Darkness enough. Having seen it alternately on DVD and streaming services, I was blown away by how clean the film looked, how clear its black levels were and how detailed the low-budget film could look at times. Carpenter has enjoyed a solid spate of Blu-Ray releases lately, and Shout! Factory's Scream sublabel seems hellbent on giving us as many of his films in good condition as possible. Add in some solid extras (all Carpenter commentaries are great affairs) and you've got an essential release for genre fans.

Read my full post at Slant.

Read my full post at Slant.

Labels:

Donald Pleasence,

DVD/Blu-Ray,

John Carpenter,

Slant Magazine

Tuesday, October 15, 2013

Alain Badiou — In Praise of Love

As Badiou lays out in the early portions of his chat with Truong, love relies on risk, the cautious willingness of both parties to expose themselves to someone different. That in and of itself is not a particularly bold observation, but Badiou constructs philosophical language on top of a layman argument. The risk, then, is not merely rewarding for its sense of the unknown but for the very difference between people, of learning to see things “from the point of view of two and not one.” Even the ethical philosophy of Emmanuel Levinas insufficiently accounts for this radical reorientation, in Badiou’s view: Levinas sees the Other as a means for discovering the Self, but Badiou conceives of love as a means of bridging Self and Other into a shared third perspective that sees the world in an entirely different way.

Read the rest at Spectrum Culture.

Prince of Darkness (John Carpenter, 1987)

My initial review of Prince of Darkness was mostly negative, but it is the Carpenter film I have returned to most often, and the one that has gradually emerged as my favorite of his. I was glad to get the chance to re-evaluate it, and though this is a belated link, it fits nicely within October viewing. I highly recommend the film, and its new Blu-Ray, which I also reviewed and will link to shortly.

Read my post at Spectrum Culture.

Read my post at Spectrum Culture.

Netflix Instant Picks (9/20—9/26)

Here's my final set of Netflix picks for Movie Mezzanine. I'll now be covering good finds on Warner Archive's excellent instant service. Check out my picks.

An American in Paris (Vincente Minnelli, 1951)

Yet if Singin’ in the Rain offers the more appealing, fluid movie, An American in Paris surpasses it as a work of filmmaking for its own sake. In Singin’, Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly’s effusive, colorful frames compose around the dancers, an understandable artistic decision and one that does not preclude well-crafted mise-en-scène. But Minnelli’s film is on another level, a union of body and camera that wholeheartedly embraces the gaudy heights of pure cinema that Singin’ occasionally keeps at arm’s length with winking acknowledgements.

Read the rest at Spectrum Culture.

Keep Your Right Up (Jean-Luc Godard, 1987)

Mostly shot before King Lear but not completed and released until after that film’s Cannes premiere, Soigne ta droite, a.k.a. Keep Your Right Up, represents something of a bridge between Detective’s larkish return to Godard’s early days of cinephilic moviemaking and the denser treatise on creation and artistic martyrdom captured in his Lear. Pop Art colors explode in a throwback to the director’s first color work, while a convoluted array of image and sound editing continues to parlay Godard’s innovative video techniques back into film, as ever focused on the material elements of filmmaking as said elements also fold into the director’s preoccupations with artistic creation.

As much as King Lear, with its literal apocalyptic backdrop, Keep Your Right Up depicts the act of creation as an act of self-annihilation, externalizing an interior conflict through a dizzying, confounding use of form. If so much of Godard’s “return” to cinema parallels the films of his original run, then this so often recalls Weekend, tipping its cap toward specific plot elements, especially an ancillary plot of Jane Birkin and her boyfriend shooting off toward Paris in a Mercedes especially recalls the earlier film’s narrative. More generally, this film touches upon its loose ancestor’s destructive impulses of creation while also updating that film’s nihilistic, politicized conclusion for an older, more reflective filmmaker.

As much as King Lear, with its literal apocalyptic backdrop, Keep Your Right Up depicts the act of creation as an act of self-annihilation, externalizing an interior conflict through a dizzying, confounding use of form. If so much of Godard’s “return” to cinema parallels the films of his original run, then this so often recalls Weekend, tipping its cap toward specific plot elements, especially an ancillary plot of Jane Birkin and her boyfriend shooting off toward Paris in a Mercedes especially recalls the earlier film’s narrative. More generally, this film touches upon its loose ancestor’s destructive impulses of creation while also updating that film’s nihilistic, politicized conclusion for an older, more reflective filmmaker.

Thursday, October 10, 2013

I Married a Witch (René Clair, 1942)

Over at Film.com, I've got a review up for René Clair's light but pleasing comedy I Married a Witch, out now from Criterion. It's a bit of a weak film, with obvious tensions behind the camera and a script that left some connective tissue unwritten among all the people who had a hand in it (as far as I can tell, after Lake's character takes a love potion, she is simply smitten from that moment on, with no snapping out of it). Still, Lake's a bombshell and Clair's delicate touch gets some elegant laughs out of situations that might have otherwise played too much on the effects.

My full review is up at Film.com.

My full review is up at Film.com.

Tuesday, October 8, 2013

Suspiria (Dario Argento, 1977)

The following is October's entry in my (much-delayed) Blind Spots series.

Dario Argento’s Suspiria is a film that only lets its audience know what is going on mere minutes before it concludes, yet provides more than sufficient immersion into its world within seconds. The director sets his tone without monsters or suspense, merely an insert shot that occurs as soon as Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper), an American student bound for a German dance academy, leaves a Munich airport in the film’s opening. As she exits, Argento cuts to a close-up of the automatic door’s locking mechanism hissing open and folding back into place, a tossed-off flourish that communicates such blithe menace that one is instantly primed for both the film’s horror, and its effervescent embrace of the extremes that horror can explore.

Dario Argento’s Suspiria is a film that only lets its audience know what is going on mere minutes before it concludes, yet provides more than sufficient immersion into its world within seconds. The director sets his tone without monsters or suspense, merely an insert shot that occurs as soon as Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper), an American student bound for a German dance academy, leaves a Munich airport in the film’s opening. As she exits, Argento cuts to a close-up of the automatic door’s locking mechanism hissing open and folding back into place, a tossed-off flourish that communicates such blithe menace that one is instantly primed for both the film’s horror, and its effervescent embrace of the extremes that horror can explore.

Monday, October 7, 2013

Captain Phillips (Paul Greengrass, 2013)

The stretch of Captain Phillips in which the Maersk Alabama container ship is approached, boarded and scoured by pirates, suits the contours of Paul Greengrass’ well-honed aesthetic to a tee. His style of assembling a sequence from coverage—if one can call his disorienting, close-proximity, handheld movements “coverage” of anything but synecdochical fragments of actors’ bodies—matches the bewilderment of a ship crew untrained and unprepared for a potential combat situation suddenly thrust into a scenario for which they have only ever drilled with perfunctory remove.

Better than most, Greengrass understands the potential to enact the hyperactive “chaos cinema” he helped popularize along a kind of gestural cinema. Thus the action segments, in which the camera jolts and snakes after a noise, or steps unthinkingly with a barefoot pirate into a room filled with broken glass, actually achieve the style’s presumed level of intimacy. In Greengrass’ hands, the shakycam aesthetic truly can make one feel like one of the crew as they mount their unarmed and exposed defense.

Better than most, Greengrass understands the potential to enact the hyperactive “chaos cinema” he helped popularize along a kind of gestural cinema. Thus the action segments, in which the camera jolts and snakes after a noise, or steps unthinkingly with a barefoot pirate into a room filled with broken glass, actually achieve the style’s presumed level of intimacy. In Greengrass’ hands, the shakycam aesthetic truly can make one feel like one of the crew as they mount their unarmed and exposed defense.

Better than most, Greengrass understands the potential to enact the hyperactive “chaos cinema” he helped popularize along a kind of gestural cinema. Thus the action segments, in which the camera jolts and snakes after a noise, or steps unthinkingly with a barefoot pirate into a room filled with broken glass, actually achieve the style’s presumed level of intimacy. In Greengrass’ hands, the shakycam aesthetic truly can make one feel like one of the crew as they mount their unarmed and exposed defense.

Better than most, Greengrass understands the potential to enact the hyperactive “chaos cinema” he helped popularize along a kind of gestural cinema. Thus the action segments, in which the camera jolts and snakes after a noise, or steps unthinkingly with a barefoot pirate into a room filled with broken glass, actually achieve the style’s presumed level of intimacy. In Greengrass’ hands, the shakycam aesthetic truly can make one feel like one of the crew as they mount their unarmed and exposed defense.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)