[The following is a belated Blind Spots entry.]

The grainy black-and-white imagery and raw sound give Regular Lovers an impression of verité instantly belied by Philippe Garrel’s aesthetically minded composition. Often, the film resembles a documentation of experimental theater more than a recreation of the director’s memories of May ‘68, particularly in its first half. The frontloaded scenes of violent student protests are presented as flattened, static looks at both students and cops, each group set against a pitch-black void as they shuffle nervously from side to side rather than in deep recess toward the opposition. Canned explosions and minimalist barricades only complete the oneiric vision of protest, so much so that a dream sequence of the students rendered as 18th century Jacobins almost passes by unnoticed for looking no less real than the riots in the present.

This alienated, dispassionate rendering of May ‘68 protests, the opposite of more vividly captured replications in films like Something in the Air, avoids nostalgia or belated self-justification on behalf of the author in favor of his mature reflection on the events of his youth. Regular Lovers stretches out for three hours to cover a well-worn subject in French cinema of the last 46 years, and by getting protests scenes out of the way quickly, it does not bother to tease the audience with thrills from a foregone conclusion. Other films on this subject attempt to capture the fury and defiance of youth in revolt, but this one cannot muster any excitement for so bitter a loss.

Personal blog of freelance critic Jake Cole, with exclusive content and links to writing around the Web.

Showing posts with label Blind Spots. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Blind Spots. Show all posts

Sunday, May 11, 2014

Tuesday, May 6, 2014

The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (Fritz Lang, 1933)

[The following is a belated Blind Spots entry.]

Fritz Lang stood out as the first master of sound cinema by making talkies that, ironically, seemed quieter than his silent epics. Films like Die Nibelungen and Metropolis are gargantuan affairs with so many moving parts that you can practically hear gears turning, set to bombastic scores of Teutonic music. Starting with M, however, the music dies, invoked only through troubling diegetic means like the killer’s whistle in that film, or the deranged humming in The Testament of Dr. Mabuse. Even in Lang’s Hollywood films, where a score is imposed, there are moments of eerie silence, none more gripping than in the opening of 1941’s Man Hunt. In the place of bombastic music, that felt sound of machinery from the silent films can now be literally heard; the first scene of Testament, for example, takes place in a printing press, the roar of printers rocking the room and sounding like a train about to burst through the walls.

Fritz Lang stood out as the first master of sound cinema by making talkies that, ironically, seemed quieter than his silent epics. Films like Die Nibelungen and Metropolis are gargantuan affairs with so many moving parts that you can practically hear gears turning, set to bombastic scores of Teutonic music. Starting with M, however, the music dies, invoked only through troubling diegetic means like the killer’s whistle in that film, or the deranged humming in The Testament of Dr. Mabuse. Even in Lang’s Hollywood films, where a score is imposed, there are moments of eerie silence, none more gripping than in the opening of 1941’s Man Hunt. In the place of bombastic music, that felt sound of machinery from the silent films can now be literally heard; the first scene of Testament, for example, takes place in a printing press, the roar of printers rocking the room and sounding like a train about to burst through the walls.

Labels:

1933,

Blind Spots,

Fritz Lang

Friday, January 24, 2014

Ugetsu (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1953)

[The following is a belated entry in last year's Blind Spots series.]

The rhyming book-end shots that open and close Ugetsu—the first shot an out-to-in establishment of a village that hones in on its main characters, the final one a move outward from those who remain to that same village horrifically altered—tidily summarize the intricate formal arrangement of Kenji Mizoguchi’s masterpiece, their inverse compositions and movements indicative of the thorough visual mapping of the entire film. The early shots are almost literally straightforward, with camera setups that view its laterally arranged characters from perpendicular positions. These compositions match the bluntness of the narrative setup: Genjuro (Masayuki Mori), a local potter, sets out with his friend Tobei (Eitaro Ozawa) to sell his wares in neighboring areas as a civil war heats up between rival daimyo. Genjuro’s wife, Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka), frets about him going to cities filled with soldiers, but otherwise their lives are tranquil.

The rhyming book-end shots that open and close Ugetsu—the first shot an out-to-in establishment of a village that hones in on its main characters, the final one a move outward from those who remain to that same village horrifically altered—tidily summarize the intricate formal arrangement of Kenji Mizoguchi’s masterpiece, their inverse compositions and movements indicative of the thorough visual mapping of the entire film. The early shots are almost literally straightforward, with camera setups that view its laterally arranged characters from perpendicular positions. These compositions match the bluntness of the narrative setup: Genjuro (Masayuki Mori), a local potter, sets out with his friend Tobei (Eitaro Ozawa) to sell his wares in neighboring areas as a civil war heats up between rival daimyo. Genjuro’s wife, Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka), frets about him going to cities filled with soldiers, but otherwise their lives are tranquil.

The rhyming book-end shots that open and close Ugetsu—the first shot an out-to-in establishment of a village that hones in on its main characters, the final one a move outward from those who remain to that same village horrifically altered—tidily summarize the intricate formal arrangement of Kenji Mizoguchi’s masterpiece, their inverse compositions and movements indicative of the thorough visual mapping of the entire film. The early shots are almost literally straightforward, with camera setups that view its laterally arranged characters from perpendicular positions. These compositions match the bluntness of the narrative setup: Genjuro (Masayuki Mori), a local potter, sets out with his friend Tobei (Eitaro Ozawa) to sell his wares in neighboring areas as a civil war heats up between rival daimyo. Genjuro’s wife, Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka), frets about him going to cities filled with soldiers, but otherwise their lives are tranquil.

The rhyming book-end shots that open and close Ugetsu—the first shot an out-to-in establishment of a village that hones in on its main characters, the final one a move outward from those who remain to that same village horrifically altered—tidily summarize the intricate formal arrangement of Kenji Mizoguchi’s masterpiece, their inverse compositions and movements indicative of the thorough visual mapping of the entire film. The early shots are almost literally straightforward, with camera setups that view its laterally arranged characters from perpendicular positions. These compositions match the bluntness of the narrative setup: Genjuro (Masayuki Mori), a local potter, sets out with his friend Tobei (Eitaro Ozawa) to sell his wares in neighboring areas as a civil war heats up between rival daimyo. Genjuro’s wife, Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka), frets about him going to cities filled with soldiers, but otherwise their lives are tranquil.

Labels:

Blind Spots,

Kenji Mizoguchi

Tuesday, January 7, 2014

All That Jazz (Bob Fosse, 1979)

[The following is a belated entry in last year's Blind Spots series.]

All That Jazz is a New Hollywood film from an Old Hollywood filmmaker; more than that, it’s a film that so thoroughly ticks off all the aesthetic and tonal properties of the American New Wave that one is left to think that New Hollywood would have been commonplace far earlier but for the intervention of moral censors and artistically conservative studio producers. Bob Fosse’s semi-autobiographical film opens with his avatar, Joe Gideon (Roy Scheider), starting his day to a montage of classical music, Alka Seltzer, eyedrops and dexies, a wake-me-up that does not prevent him from lolling in the shower with a soaked cigarette limply dangling from his lips. Red-eyed and weary, Joe nevertheless looks as good as he ever will in this movie, as his increasingly stressful work schedule and the accumulated residue of his hard living start to crush him physically and emotionally.

All That Jazz is a New Hollywood film from an Old Hollywood filmmaker; more than that, it’s a film that so thoroughly ticks off all the aesthetic and tonal properties of the American New Wave that one is left to think that New Hollywood would have been commonplace far earlier but for the intervention of moral censors and artistically conservative studio producers. Bob Fosse’s semi-autobiographical film opens with his avatar, Joe Gideon (Roy Scheider), starting his day to a montage of classical music, Alka Seltzer, eyedrops and dexies, a wake-me-up that does not prevent him from lolling in the shower with a soaked cigarette limply dangling from his lips. Red-eyed and weary, Joe nevertheless looks as good as he ever will in this movie, as his increasingly stressful work schedule and the accumulated residue of his hard living start to crush him physically and emotionally.

Labels:

1979,

Blind Spots,

Bob Fosse,

Roy Scheider

Wednesday, January 1, 2014

Blind Spots 2014

In writing terms, I had a great 2013. I added some cool new bylines to my resumé, and for the first time I even got paid for my work! As such, constantly looming deadlines made me shift focus away from this blog even to update it with links to my work, much less to actually write stuff here. I imagine that will continue in 2014 (at least I hope it does, as it means I'm still pulling down freelance work), but I am still going to try and write a few exclusives here, primarily with my entries in the cross-blog Blind Spots series. I failed to write about five of my chosen picks for 2013, even though I actually watched one of them, French Cancan (a masterpiece I will write about shortly, I hope). So, as to not forget them, I will list them here alongside this year's picks, and with any luck I will get to all of them before the year is done.

Outstanding picks:

2014's picks:

Outstanding picks:

French Cancan (Jean Renoir, 1954)

Gertrud (Carl Th. Dreyer, 1964)

Judex [a 2012(!) Blind Spot] (Louis Feuillade, 1916)

Too Early, Too Late (Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, 1982)

2014's picks:

The Beyond (Lucio Fulci, 1981)

Bombay (Mani Ratnam, 1995)

Cockfighter (Monte Hellman, 1974)

The Flowers of Shanghai (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1985)

Girlfriends (Claudia Weill, 1978)

Greed (Erich von Stroheim, 1922)

The Outlaw and His Wife (Victor Sjöstrom, 1918)

Peking Opera Blues (Tsui Hark, 1986)

Pyaasa (Guru Dutt, 1957)

Regular Lovers (Philippe Garrel, 2005)

The Terrorizers (Edward Yang, 1986)

Labels:

Blind Spots

Saturday, December 28, 2013

The Long Goodbye (Robert Altman, 1973)

[The following is a belated Blind Spots entry.]

The precision of Raymond Chandler’s prose is rendered almost sleepily in Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye, trading the laconic for the lethargic. “Rip van Winkle” is what the filmmaker termed his version of Chandler’s most iconic creation in reference to how Elliot Gould’s Marlowe is a 1953 detective carrying on according to his period as he roams the radically different America of 1973, yet the sobriquet could equally apply to how punch-drunk, confused and tired Gould plays the part. Chandler’s books may have been mysteries, but like the best of pulp fiction they were intensely focused. The Long Goodbye, on the other hand, ambles along in confusion, puncturing Marlowe’s hard-boiled competence as both the narrative and even the cinematography seem unable to focus on anything, much less the task at hand.

The precision of Raymond Chandler’s prose is rendered almost sleepily in Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye, trading the laconic for the lethargic. “Rip van Winkle” is what the filmmaker termed his version of Chandler’s most iconic creation in reference to how Elliot Gould’s Marlowe is a 1953 detective carrying on according to his period as he roams the radically different America of 1973, yet the sobriquet could equally apply to how punch-drunk, confused and tired Gould plays the part. Chandler’s books may have been mysteries, but like the best of pulp fiction they were intensely focused. The Long Goodbye, on the other hand, ambles along in confusion, puncturing Marlowe’s hard-boiled competence as both the narrative and even the cinematography seem unable to focus on anything, much less the task at hand.

Labels:

1973,

Blind Spots,

Elliot Gould,

Robert Altman,

Sterling Hayden

Tuesday, October 8, 2013

Suspiria (Dario Argento, 1977)

The following is October's entry in my (much-delayed) Blind Spots series.

Dario Argento’s Suspiria is a film that only lets its audience know what is going on mere minutes before it concludes, yet provides more than sufficient immersion into its world within seconds. The director sets his tone without monsters or suspense, merely an insert shot that occurs as soon as Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper), an American student bound for a German dance academy, leaves a Munich airport in the film’s opening. As she exits, Argento cuts to a close-up of the automatic door’s locking mechanism hissing open and folding back into place, a tossed-off flourish that communicates such blithe menace that one is instantly primed for both the film’s horror, and its effervescent embrace of the extremes that horror can explore.

Dario Argento’s Suspiria is a film that only lets its audience know what is going on mere minutes before it concludes, yet provides more than sufficient immersion into its world within seconds. The director sets his tone without monsters or suspense, merely an insert shot that occurs as soon as Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper), an American student bound for a German dance academy, leaves a Munich airport in the film’s opening. As she exits, Argento cuts to a close-up of the automatic door’s locking mechanism hissing open and folding back into place, a tossed-off flourish that communicates such blithe menace that one is instantly primed for both the film’s horror, and its effervescent embrace of the extremes that horror can explore.

Labels:

1977,

Blind Spots,

Dario Argento

Monday, May 27, 2013

Elephant (Gus Van Sant, 2003)

The following is my May entry for Blindspots.

Elephant’s Steadicam tracks last so long and move so languidly that they frequently curve backward in time, each shift of character focus drifting back a few minutes or a few hours to show the parallel movement of different students as they cross each other’s paths. This structure, modeled on Béla Tarr’s Satantango, repeats shots from changing perspectives, adding new information to established scenes to reconfigure their context.

Each of these connective curves adds a third dimension to configurations, not merely illuminating the interlocking nature of seemingly disparate clusters of students within a confined space but the emotional states of those previously seen in glimpses or even longer takes that nevertheless failed to reveal something as simple as the tears in the eyes of a boy who just endured a tongue-lashing because he could not bring himself to put the deserved blame for his tardiness on his alcoholic father. Incessant close-ups and frantic editing are regularly singled out for their obscuring qualities, but distance and shot length cannot by itself bring clarity.

Elephant’s Steadicam tracks last so long and move so languidly that they frequently curve backward in time, each shift of character focus drifting back a few minutes or a few hours to show the parallel movement of different students as they cross each other’s paths. This structure, modeled on Béla Tarr’s Satantango, repeats shots from changing perspectives, adding new information to established scenes to reconfigure their context.

Each of these connective curves adds a third dimension to configurations, not merely illuminating the interlocking nature of seemingly disparate clusters of students within a confined space but the emotional states of those previously seen in glimpses or even longer takes that nevertheless failed to reveal something as simple as the tears in the eyes of a boy who just endured a tongue-lashing because he could not bring himself to put the deserved blame for his tardiness on his alcoholic father. Incessant close-ups and frantic editing are regularly singled out for their obscuring qualities, but distance and shot length cannot by itself bring clarity.

Labels:

2003,

Blind Spots,

Gus Van Sant

Tuesday, April 30, 2013

Duelle (Jacques Rivette, 1976)

The following is my April submission for Blindspots.

The first of an aborted quartet of planned films that variated on the same theme, Jacques Rivette’s Duelle (une quarantaine) is a noir-cum-sci-fi fantasia, a tale of goddesses locked in an immortal struggle for the right to be mortal that plays out in an oblique homage to the films of the 1940s. Dividing its four central women into various generic archetypes, Duelle then pits them against each other in a series of frictive encounters that gradually push characters outside their oppositional definitions and into new binaries until Rivette breaks through to areas outside constrictive either/or boundaries.

Even the film’s basic conceit operates on two levels filled with their own distinct dialectics. The quest for a precious diamond juxtaposes naïve bystanders (Hermine Karagheuz’s Lucie) and manipulated molls (Nicole Garcia’s Elsa, née Jeanne) against more duplicitous criminal elements (Juliet Berto’s Leni and Bulle Ogier’s Viva) in classic noir terms that fit the MacGuffin in with such coveted items as the Maltese Falcon. But the diamond itself carries mystical properties, capable of granting godhood to mortals and vice-versa, adding fantastical oppositions of mortal/immortal and sun/moon.

The first of an aborted quartet of planned films that variated on the same theme, Jacques Rivette’s Duelle (une quarantaine) is a noir-cum-sci-fi fantasia, a tale of goddesses locked in an immortal struggle for the right to be mortal that plays out in an oblique homage to the films of the 1940s. Dividing its four central women into various generic archetypes, Duelle then pits them against each other in a series of frictive encounters that gradually push characters outside their oppositional definitions and into new binaries until Rivette breaks through to areas outside constrictive either/or boundaries.

Even the film’s basic conceit operates on two levels filled with their own distinct dialectics. The quest for a precious diamond juxtaposes naïve bystanders (Hermine Karagheuz’s Lucie) and manipulated molls (Nicole Garcia’s Elsa, née Jeanne) against more duplicitous criminal elements (Juliet Berto’s Leni and Bulle Ogier’s Viva) in classic noir terms that fit the MacGuffin in with such coveted items as the Maltese Falcon. But the diamond itself carries mystical properties, capable of granting godhood to mortals and vice-versa, adding fantastical oppositions of mortal/immortal and sun/moon.

Labels:

Blind Spots,

Jacques Rivette

Tuesday, March 26, 2013

By The Bluest of Seas (Boris Barnet, 1936)

The following is my March entry for Blindspots.

By the Bluest of Seas begins and ends on the same images, possibly even the same shots. But the roaring waves of the Caspian Sea, and gulls taking flight against a sun bursting through clouds, emit oppositional moods at each bookend. At the start, the shots of the stirred ocean connote the sea’s unforgiving power, having destroyed a ship off-screen and whipping its surviving sailors, Yusuf (Lev Sverdlin) and Aloysha (Nikolai Kryuchkov), around like rag dolls. When they return to these churning waters at the conclusion, however, the Caspian both reflects the final release of the emotions put on forthright display in the intervening story as well as an unexpectedly warm homecoming for two men who belong on the water.

For as merciless as the sea can be, its mercurial nature can also make it warm and inviting. Once the storm calms, director Boris Barnet replaces the ominous shots of waves crashing upon each other with ones of sun-kissed surfaces glinting in the light of day, with a single wave gently rolling along like a pulse. The serenity of it relieves as much as the appearance of a boat to rescue Aloysha and Yusuf, who are taken to the nearby “Lights of the Communism” kolkhoz and gladly volunteer to help man the village’s fishing vessels. Here the film might have slipped into a censor-friendly paean to Soviet labor were the adoptive workers not instantly stricken by the sight of a woman.

By the Bluest of Seas begins and ends on the same images, possibly even the same shots. But the roaring waves of the Caspian Sea, and gulls taking flight against a sun bursting through clouds, emit oppositional moods at each bookend. At the start, the shots of the stirred ocean connote the sea’s unforgiving power, having destroyed a ship off-screen and whipping its surviving sailors, Yusuf (Lev Sverdlin) and Aloysha (Nikolai Kryuchkov), around like rag dolls. When they return to these churning waters at the conclusion, however, the Caspian both reflects the final release of the emotions put on forthright display in the intervening story as well as an unexpectedly warm homecoming for two men who belong on the water.

For as merciless as the sea can be, its mercurial nature can also make it warm and inviting. Once the storm calms, director Boris Barnet replaces the ominous shots of waves crashing upon each other with ones of sun-kissed surfaces glinting in the light of day, with a single wave gently rolling along like a pulse. The serenity of it relieves as much as the appearance of a boat to rescue Aloysha and Yusuf, who are taken to the nearby “Lights of the Communism” kolkhoz and gladly volunteer to help man the village’s fishing vessels. Here the film might have slipped into a censor-friendly paean to Soviet labor were the adoptive workers not instantly stricken by the sight of a woman.

Labels:

1936,

Blind Spots,

Boris Barnet

Tuesday, February 5, 2013

Trash (Paul Morrissey, 1970)

Man, I've got to get better about updating this place with links. My review for Paul Morrissey's excellent, transgressive Trash (my first Blindspot entry of the year) has been up for some time at Movie Mezzanine, but I forgot to link to it here. Suffice to say, it's a brilliant, blistering film that also finds an empathy through its actors that the camera otherwise would not communicate. Highly recommended.

My full piece is up at Movie Mezzanine.

My full piece is up at Movie Mezzanine.

Labels:

Blind Spots,

Movie Mezzanine,

Paul Morrissey

Tuesday, January 22, 2013

The Long Day Closes (Terence Davies, 1992)

This is my unforgivably late Blind Spots entry for last November. December's pick, Feuillade's Judex, will likely not receive a write-up until next month. However, this month's scheduled Blind Spots piece will appear on time.

The Long Day Closes opens like a classic movie, with the credits appearing before the picture instead of after and playing over a styled image. In this case, it is a still life of some flowers off to the left as credits appear in flowing cursive in the right two-thirds of the screen. When the movie proper begins, it is to the 20th Century Fox fanfare blared over a brick wall with a plaque announcing the film’s setting on Kensington Street. The juxtaposition deftly pre-summarizes the film, in which the still life recreations of postwar Liverpool are enlivened by the joys of cinema that not only give its child protagonist some kind of escape in a dreary community but are internalized and re-emitted to make that world livable.

The boy in question is Bud, an unassuming chap whom Davies regularly places directly in the center of the frame, surrounding him with symmetrical arrangements of people and objects. The dank, dirty brick walls of this industrial port town lend the film shades of neo-realism, but as with the more brutally forthright Distant Voices, Still Lives, such mise-en-scène adds a lyrical, formal quality to what might have been kitchen-sink aesthetics. The falsity of the image is blatant, but that also informs so much of the film’s deeply felt approach to memory.

The Long Day Closes opens like a classic movie, with the credits appearing before the picture instead of after and playing over a styled image. In this case, it is a still life of some flowers off to the left as credits appear in flowing cursive in the right two-thirds of the screen. When the movie proper begins, it is to the 20th Century Fox fanfare blared over a brick wall with a plaque announcing the film’s setting on Kensington Street. The juxtaposition deftly pre-summarizes the film, in which the still life recreations of postwar Liverpool are enlivened by the joys of cinema that not only give its child protagonist some kind of escape in a dreary community but are internalized and re-emitted to make that world livable.

The boy in question is Bud, an unassuming chap whom Davies regularly places directly in the center of the frame, surrounding him with symmetrical arrangements of people and objects. The dank, dirty brick walls of this industrial port town lend the film shades of neo-realism, but as with the more brutally forthright Distant Voices, Still Lives, such mise-en-scène adds a lyrical, formal quality to what might have been kitchen-sink aesthetics. The falsity of the image is blatant, but that also informs so much of the film’s deeply felt approach to memory.

Labels:

Blind Spots,

Terence Davies

Tuesday, January 1, 2013

Blindspots 2013

It may be presumptuous of me to plan for another year's worth of Blindspots posts when I still have two more from 2012 to complete (expect one for The Long Day Closes within a week and Judex...well, later). Still, these are some films I've meant to watch for some time, so perhaps writing them down here will prompt me to get to them. As with last year, I'll cover one a month at random (save for the horror film meant for October). The films are as follows:

All That Jazz (Bob Fosse, 1979)

French Cancan (Jean Renoir, 1955)

Gertrud (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1964)

Too Early, Too Late (Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, 1982)

Ugetsu (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1953)

Labels:

Blind Spots

Tuesday, December 4, 2012

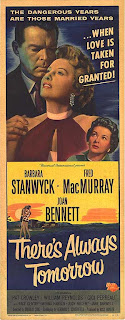

There's Always Tomorrow (Douglas Sirk, 1956)

[The following is my belated October entry for Blind Spots. I hope to catch up on last months and watch my final pick for the year on time.]

Clifford Groves (Fred MacMurray) has made a life of modest prosperity for himself. He has built a reasonably sized toy manufacturer from the ground up, offering him enough affluence to afford a nice house and a servant to help around it. Unlike Douglas Sirk’s “women’s pictures,” There’s Always Tomorrow remains with Cliff, who, in darkly amusing irony, is everything the husbands in those other melodramas is not. A decent, hard worker and a loving family man, Cliff is not the tyrant of his household but the ideal vision of the postwar American man. And yet, he exists in a prison as much the housewives who dot typical domestic dramas from the period, caged not by abuse but neglect, objectified not as a provider of care but of material sustenance.

Sirk inverts the usual dynamics of melodrama to tell Cliff’s story. The director wanted to shoot the movie in color but could not secure the money to do so. Nevertheless, Russell Metty’s black-and-white cinematography visualizes the different social pressures and archetypes at work on men. The emotive, visceral use of color is thus swapped for a kind of remove, denying Cliff an aesthetic outlet for his feelings to ensure he does not have any unmanly outbursts. Deep focus shots capture the vastness of the home’s interiors, and the cold space they create emphasizes how stark and dead the middle-class comfort around the man has become.

Clifford Groves (Fred MacMurray) has made a life of modest prosperity for himself. He has built a reasonably sized toy manufacturer from the ground up, offering him enough affluence to afford a nice house and a servant to help around it. Unlike Douglas Sirk’s “women’s pictures,” There’s Always Tomorrow remains with Cliff, who, in darkly amusing irony, is everything the husbands in those other melodramas is not. A decent, hard worker and a loving family man, Cliff is not the tyrant of his household but the ideal vision of the postwar American man. And yet, he exists in a prison as much the housewives who dot typical domestic dramas from the period, caged not by abuse but neglect, objectified not as a provider of care but of material sustenance.

Sirk inverts the usual dynamics of melodrama to tell Cliff’s story. The director wanted to shoot the movie in color but could not secure the money to do so. Nevertheless, Russell Metty’s black-and-white cinematography visualizes the different social pressures and archetypes at work on men. The emotive, visceral use of color is thus swapped for a kind of remove, denying Cliff an aesthetic outlet for his feelings to ensure he does not have any unmanly outbursts. Deep focus shots capture the vastness of the home’s interiors, and the cold space they create emphasizes how stark and dead the middle-class comfort around the man has become.

Labels:

1956,

Barbara Stanwyck,

Blind Spots,

Douglas Sirk,

Fred MacMurray,

Joan Bennett

Monday, October 1, 2012

Center Stage (Stanley Kwan, 1992)

[The following is my Blind Spots review for September]

Using period-appropriate filming techniques for movies set in the 20th century is hardly new, especially in the use of melodramatic lighting and color. But Stanley Kwan's Center Stage (a.k.a. Actress) actually incorporates the techniques into the film at hand, the biopic of 1930s star Ruan Ling-yu doubling as a recreation of both period-appropriate Chinese melodrama and the postwar American melodrama as practiced by Sirk, Ray et al. By going outside the stylistic touches of the film's time to broadly canvas melodrama as a fluid, evolving, international artform and expression. As if to to prove to the audience why they should care for the film's subject, Kwan establishes the artistic worth of the medium and genre in which she worked.

Yet this also sets the stage for Kwan to show how the films in which Ruan gained her fame—tales of harassed and martyred women misunderstood and abused by social forces and an ignorant mob—were reflected in the tragedy of her short life. Her penultimate film, New Women, portrayed the press as an insensitive pack of jackals who drove a women to her suicide, an outrage that prompted vindictive newspapers to...drive this woman to her suicide. It is a twisted irony, and the director adds a layer of his own by including black-and-white scenes of himself and the actors as themselves, discussing their "characters" and interviewing surviving members of the Chinese film industry who worked with the actress. The film's first scene depicts Kwan explaining Ruan's career arc, which began with minor roles in fluff before she went to a film studio that prided itself on more progressive, artistic work and her career exploded. Maggie Cheung, who plays Ruan, notes with a laugh that her own path recalls Ruan. In another case of life imitating art, Cheung would use this very part to transition from supporting roles to becoming one of the most respected actresses on the international stage. When making a film biography of a film star, one supposes that self-reflexivity is unavoidable.

Using period-appropriate filming techniques for movies set in the 20th century is hardly new, especially in the use of melodramatic lighting and color. But Stanley Kwan's Center Stage (a.k.a. Actress) actually incorporates the techniques into the film at hand, the biopic of 1930s star Ruan Ling-yu doubling as a recreation of both period-appropriate Chinese melodrama and the postwar American melodrama as practiced by Sirk, Ray et al. By going outside the stylistic touches of the film's time to broadly canvas melodrama as a fluid, evolving, international artform and expression. As if to to prove to the audience why they should care for the film's subject, Kwan establishes the artistic worth of the medium and genre in which she worked.

Yet this also sets the stage for Kwan to show how the films in which Ruan gained her fame—tales of harassed and martyred women misunderstood and abused by social forces and an ignorant mob—were reflected in the tragedy of her short life. Her penultimate film, New Women, portrayed the press as an insensitive pack of jackals who drove a women to her suicide, an outrage that prompted vindictive newspapers to...drive this woman to her suicide. It is a twisted irony, and the director adds a layer of his own by including black-and-white scenes of himself and the actors as themselves, discussing their "characters" and interviewing surviving members of the Chinese film industry who worked with the actress. The film's first scene depicts Kwan explaining Ruan's career arc, which began with minor roles in fluff before she went to a film studio that prided itself on more progressive, artistic work and her career exploded. Maggie Cheung, who plays Ruan, notes with a laugh that her own path recalls Ruan. In another case of life imitating art, Cheung would use this very part to transition from supporting roles to becoming one of the most respected actresses on the international stage. When making a film biography of a film star, one supposes that self-reflexivity is unavoidable.

Labels:

1992,

Blind Spots,

Carina Lau,

Maggie Cheung,

Stanley Kwan,

Tony Leung Chiu-Wai

Tuesday, July 31, 2012

Some Came Running (Vincente Minnelli, 1958)

[The following is my July entry for Blind Spots.]

Some Came Running opens with antithetical moods. Lush but subtle color paints the bus ride of a soldier returning from World War II in warmth, a gentle portrait of the prodigal son on his journey back home. But the CinemaScope framing and portentous music from Elmer Bernstein undercuts this sense of idyll, inserting a sense of tension and conflict before anything has happened. The incongruity of these moods instantly undermines any audience expectation and generating a level of uncertainty in what will follow. For another filmmaker, such unsure footing might be the sign of weak technique and structure, but Vincente Minnelli ingeniously sets to undermining his own frame before he's put anything of note into it.

Soon, the tension becomes clear. The bus driver wakes the soldier, Dave Hirsh (Frank Sinatra), whose grogginess turns to sober apprehension when he learns he has been brought back to his hometown. When he gets off the bus, a ditzy Chicago girl, Ginny (Shirley MacLaine), gets off with him, mentioning how he was so good as to rough up her abusive boyfriend back in Chicago and bring her along. Dave's bewilderment over her, and his clearly unwelcome return home, reveal that this ostensibly happy moment is the result of a night of blackout drinking. As Dave puts up in a nearby hotel until he can figure out what to do, he finds himself drawn into a world dictated by insipid proprietary norms and both undercut and fundamentally supported by a vulgar underground.

Some Came Running opens with antithetical moods. Lush but subtle color paints the bus ride of a soldier returning from World War II in warmth, a gentle portrait of the prodigal son on his journey back home. But the CinemaScope framing and portentous music from Elmer Bernstein undercuts this sense of idyll, inserting a sense of tension and conflict before anything has happened. The incongruity of these moods instantly undermines any audience expectation and generating a level of uncertainty in what will follow. For another filmmaker, such unsure footing might be the sign of weak technique and structure, but Vincente Minnelli ingeniously sets to undermining his own frame before he's put anything of note into it.

Soon, the tension becomes clear. The bus driver wakes the soldier, Dave Hirsh (Frank Sinatra), whose grogginess turns to sober apprehension when he learns he has been brought back to his hometown. When he gets off the bus, a ditzy Chicago girl, Ginny (Shirley MacLaine), gets off with him, mentioning how he was so good as to rough up her abusive boyfriend back in Chicago and bring her along. Dave's bewilderment over her, and his clearly unwelcome return home, reveal that this ostensibly happy moment is the result of a night of blackout drinking. As Dave puts up in a nearby hotel until he can figure out what to do, he finds himself drawn into a world dictated by insipid proprietary norms and both undercut and fundamentally supported by a vulgar underground.

Labels:

1958,

Blind Spots,

Dean Martin,

Frank Sinatra,

Shirley MacLaine,

Vincente Minnelli

Tuesday, June 26, 2012

The Best Years of Our Lives (William Wyler, 1946)

[The following is my June entry for Blind Spots.]

More than one person has referred to William Wyler's The Best Years of Our Lives as the "best" Best Picture winner. What many failed to mention is that it is also the "most" Best Picture winner. It resembles almost the quintessential essence of the ideal Oscar movie: socially conscious but inoffensive, heart-wrenching on a surface level, and beautiful without being a true aesthetic marvel. But if the film represents the non plus ultra of Academy-pleasing filmmaking, it is also a demonstration of how great that kind of movie can be. Wyler's direction, aided by the great Gregg Toland, may not be fussy, but its framing offers direct snapshots of character insight that never let the pace lag on this three-hour extravaganza of post-war moralism.

The Best Years of Our Lives opens at a military post on an airstrip that houses soldiers, seamen and pilots waiting in limbo for an open plane seat to take them back home after the end of World War II. As they all wait for the chance to finally go home, rich civilians continue to fly undisturbed, not one inconvenienced for the sake of sending America's heroes back to their loved ones. At last, Fred Derry (Dana Andrews), an Air Force captain, manages to get his ride back to the Midwestern Boone City along with a sailor named Homer Parrish (Harold Russell). But the jovial, amusing tone of this cramped purgatory and the promise of a return to normalcy dies when Parrish goes to sign his name to get on the plane and reveals two prosthetic hooks where his hands used to be. The medium long shot remains unbroken as both Fred and the man in charge of scheduling instantly shrivel with pity, and the tone of the film, only subtly undermined to this point, instantly changes. Homer and Fred meet the last lead, Army sergeant Al Stephenson (Fredric March) on the plane ride home, and despite their rapport, it's clear that all three are as nervous to go home as excited.

More than one person has referred to William Wyler's The Best Years of Our Lives as the "best" Best Picture winner. What many failed to mention is that it is also the "most" Best Picture winner. It resembles almost the quintessential essence of the ideal Oscar movie: socially conscious but inoffensive, heart-wrenching on a surface level, and beautiful without being a true aesthetic marvel. But if the film represents the non plus ultra of Academy-pleasing filmmaking, it is also a demonstration of how great that kind of movie can be. Wyler's direction, aided by the great Gregg Toland, may not be fussy, but its framing offers direct snapshots of character insight that never let the pace lag on this three-hour extravaganza of post-war moralism.

The Best Years of Our Lives opens at a military post on an airstrip that houses soldiers, seamen and pilots waiting in limbo for an open plane seat to take them back home after the end of World War II. As they all wait for the chance to finally go home, rich civilians continue to fly undisturbed, not one inconvenienced for the sake of sending America's heroes back to their loved ones. At last, Fred Derry (Dana Andrews), an Air Force captain, manages to get his ride back to the Midwestern Boone City along with a sailor named Homer Parrish (Harold Russell). But the jovial, amusing tone of this cramped purgatory and the promise of a return to normalcy dies when Parrish goes to sign his name to get on the plane and reveals two prosthetic hooks where his hands used to be. The medium long shot remains unbroken as both Fred and the man in charge of scheduling instantly shrivel with pity, and the tone of the film, only subtly undermined to this point, instantly changes. Homer and Fred meet the last lead, Army sergeant Al Stephenson (Fredric March) on the plane ride home, and despite their rapport, it's clear that all three are as nervous to go home as excited.

Labels:

Blind Spots,

Dana Andrews,

Teresa Wright,

William Wyler

Sunday, May 27, 2012

Irma Vep (Olivier Assayas, 1996)

[This is my May post for Blind Spots.]

Irma Vep is the third Olivier Assayas film I've seen, the other two being Summer Hours and Carlos. This 1996 feature contains the roots of both, the former's elegant respect for French art history and the latter's deconstructive, post-New Wave wit. A film about a film production starring Jean-Pierre Léaud, Irma Vep instantly recalls Day for Night, but as Assayas voices and visualizes a sense of dissatisfaction with French cinema, the film becomes something else. Eric Gautier's gritty, 16mm cinematography and sophisticated camera movements combine New Wave spontaneity (the film was shot in three weeks) with formal know-how to be both behind-the-scenes docudrama and rich cinematic fantasy.

That the production in question is an adaptation of Louis Feuillade's 1915 serial Les Vampires only complicates Assayas' thematic intent. The characters working on this French film set all talk of American films, some disapprovingly, others with an eagerness to see their own national cinema reflect Hollywood's crowd-pleasing scale. Assayas "remakes" Feuillade's film to remind everyone that France invented the action epic, and that they didn't need insane budgets and special effects to do so. Yet the fact that someone would remake it speaks to a lack of original ideas for contemporary French directors, and that's leaving out how little of France seems to make its way into this production.

Irma Vep is the third Olivier Assayas film I've seen, the other two being Summer Hours and Carlos. This 1996 feature contains the roots of both, the former's elegant respect for French art history and the latter's deconstructive, post-New Wave wit. A film about a film production starring Jean-Pierre Léaud, Irma Vep instantly recalls Day for Night, but as Assayas voices and visualizes a sense of dissatisfaction with French cinema, the film becomes something else. Eric Gautier's gritty, 16mm cinematography and sophisticated camera movements combine New Wave spontaneity (the film was shot in three weeks) with formal know-how to be both behind-the-scenes docudrama and rich cinematic fantasy.

That the production in question is an adaptation of Louis Feuillade's 1915 serial Les Vampires only complicates Assayas' thematic intent. The characters working on this French film set all talk of American films, some disapprovingly, others with an eagerness to see their own national cinema reflect Hollywood's crowd-pleasing scale. Assayas "remakes" Feuillade's film to remind everyone that France invented the action epic, and that they didn't need insane budgets and special effects to do so. Yet the fact that someone would remake it speaks to a lack of original ideas for contemporary French directors, and that's leaving out how little of France seems to make its way into this production.

Labels:

Blind Spots,

Jean-Pierre Léaud,

Maggie Cheung,

Olivier Assayas

Tuesday, May 8, 2012

Birth (Jonathan Glazer, 2004)

[The following post is my belated April selection of my Blind Spots choices.]

Jonathan Glazer's Birth cribs so much from Stanley Kubrick that I don't think that even Steven Spielberg's A.I., Kubrick's own former project, owes as much to the master. A stately, graceful tracking shot follows a lecturer, Sean, as he goes on a run in Central Park after decrying the concept of reincarnation. The shot is as frigid as the snow-covered area it covers, following behind the jogging man like a stalker until, finally, the angle changes and darts in front of the man. As it does so, the camera moves back into a tunnel under a bridge as Sean slows his pace and starts to stumble. In the middle of this darkened hole, he collapses and dies of a heart attack. Somewhere else, a baby is born in a bath.

The connection is obvious. A man enters a giant womb and dies as a child emerges from one to live. The man who dismissed reincarnation is visually linked to rebirth, and soon the narrative makes this the driving focus of the film when Sean's widow, Anna (Nicole Kidman), has her slowly rebuilt life re-shattered 10 years after her husband's death when a young boy (Cameron Bright) shows up at her door claiming to be Sean. This Sean's emergence raises metaphysical questions that gradually come to nothing as Glazer icy framings serve only to keep a ludicrous, overheated melodrama on ice.

Jonathan Glazer's Birth cribs so much from Stanley Kubrick that I don't think that even Steven Spielberg's A.I., Kubrick's own former project, owes as much to the master. A stately, graceful tracking shot follows a lecturer, Sean, as he goes on a run in Central Park after decrying the concept of reincarnation. The shot is as frigid as the snow-covered area it covers, following behind the jogging man like a stalker until, finally, the angle changes and darts in front of the man. As it does so, the camera moves back into a tunnel under a bridge as Sean slows his pace and starts to stumble. In the middle of this darkened hole, he collapses and dies of a heart attack. Somewhere else, a baby is born in a bath.

The connection is obvious. A man enters a giant womb and dies as a child emerges from one to live. The man who dismissed reincarnation is visually linked to rebirth, and soon the narrative makes this the driving focus of the film when Sean's widow, Anna (Nicole Kidman), has her slowly rebuilt life re-shattered 10 years after her husband's death when a young boy (Cameron Bright) shows up at her door claiming to be Sean. This Sean's emergence raises metaphysical questions that gradually come to nothing as Glazer icy framings serve only to keep a ludicrous, overheated melodrama on ice.

Labels:

Blind Spots,

Danny Huston,

Lauren Bacall,

Nicole Kidman

Monday, March 12, 2012

Faust (F.W. Murnau, 1926)

[This is my second entry in my Blind Spots series]

F.W. Muranu's final German film, Faust, is a glorious send-off for the Hollywood-bound filmmaker. Less poetic than his prior The Last Laugh (and his subsequent Sunrise and City Girl, for that matter), Faust makes up for its relative lack of camera movement for a grandeur that could rival even Lang. It's fitting that Murnau should select for his final work in his homeland the subject of a classic German legend, more so that the film should incorporate various interpretations of that legend to fully explore the folktale.

Modeled chiefly on the first part of Goethe's interpretation of the story, Faust is a film of grandiose darkness. It begins with superimposed images of the four horsemen riding in the clouds, their skeletal figures frozen in grim war poses. Smoke appears in these first shots, as it does in most of the subsequent ones; at times it seems as if hellfire is about to set light to the projector itself. But nothing compares to the sight of Mephisto himself (Emil Jannings), a giant demon revealed in the light of an evil-banishing Archangel. Looking like a mountain with a face, Mephisto is imposing and terrifying even from the torso-up.

F.W. Muranu's final German film, Faust, is a glorious send-off for the Hollywood-bound filmmaker. Less poetic than his prior The Last Laugh (and his subsequent Sunrise and City Girl, for that matter), Faust makes up for its relative lack of camera movement for a grandeur that could rival even Lang. It's fitting that Murnau should select for his final work in his homeland the subject of a classic German legend, more so that the film should incorporate various interpretations of that legend to fully explore the folktale.

Modeled chiefly on the first part of Goethe's interpretation of the story, Faust is a film of grandiose darkness. It begins with superimposed images of the four horsemen riding in the clouds, their skeletal figures frozen in grim war poses. Smoke appears in these first shots, as it does in most of the subsequent ones; at times it seems as if hellfire is about to set light to the projector itself. But nothing compares to the sight of Mephisto himself (Emil Jannings), a giant demon revealed in the light of an evil-banishing Archangel. Looking like a mountain with a face, Mephisto is imposing and terrifying even from the torso-up.

Labels:

Blind Spots,

Emil Jannings,

F.W. Murnau

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)