One of my favorite John Ford discoveries so far is this lazy river comedy, Ford's final collaboration with Will Rogers and a wonderful example of the director's affectionate but critical view of the post-Reconstruction South. Featuring one of Stepin Fetchit's most brazenly satiric roles and a plot that regularly falls to the wayside for the sake of slice-of-life character richness, Steamboat Round the Bend is a modest but powerful display of Ford's carefully constructed subtleties and humanity.

My full review is up now at Movie Mezzanine.

Personal blog of freelance critic Jake Cole, with exclusive content and links to writing around the Web.

Sunday, March 31, 2013

Netflix Instant Picks 3/29—4/4/13

A lot of stuff has hit/will hit Netflix, and these all-new picks barely scratch the surface of the avalanche of great titles hitting streaming service. For now, though, the bevy of Cartoon Network programs should tidy over anyone.

Check out Corey's and my picks over at Movie Mezzanine.

Check out Corey's and my picks over at Movie Mezzanine.

Labels:

Movie Mezzanine,

Netflix

Friday, March 29, 2013

Wrong (Quentin Dupieux, 2013)

I can only hope I don't see a worse, uglier more self-congratulatory disaster this year than Quentin Dupieux's Wrong, his latest exercise in lead-weight unfunniness masked as pseudo-surrealism. Perhaps, like Cronenberg's perverse use of digital in Cosmopolis, the smeary video gloss, alienating movement and jolting editing is meant to be an intentional corruption of visual expectations. But Dupieux is no Cronenberg, and his own surreal vision of a soulless, capitalistic society is put forward only in laughably out-of-date workplace satire spiced up by rain falling on toiling workers. Har har. Only William Fichtner escapes from this unscathed, primarily because he cannot get through his lines fast enough in order to walk out of his one real scene. Everyone else, sadly, lets every plodding word hang in the air, hoping if they leave it there long enough, Dupieux's banal, cynical jabs may cocoon and subsequently emerge actual jokes.

My full review is up now at Movie Mezzanine.

My full review is up now at Movie Mezzanine.

Labels:

2013,

Movie Mezzanine,

Quentin Dupieux

Thursday, March 28, 2013

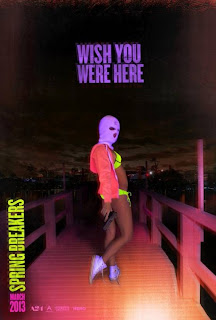

Spring Breakers (Harmony Korine, 2013)

On its face, Spring Breakers is such a quantum leap forward for Harmony Korine that it is easy to overlook what a logical progression it is for the director. Its recursive editing, not merely repeating actions but occasionally anticipating them, reflect the patterns used to chart the directionless movements of Korine’s prior characters, a loose, non-narrative structure that gradually reveals milieu over plot. His settings tend to alienate before they assimilate, and that certainly holds true for the slow-motion shots of Floridian bacchanal that open the film to the oppressive strains of Skrillex. Like a lenticular “wish you were here” card, the montage starts with innocuous shots of young adults out on the beach before a turn reveals bikini tops flying and phallically positioned beer cans pouring on women’s faces. The allure of spring break is laid bare, though Korine has barely even scratched the surface of the hell he will conjure in St. Pete.

To a group of undergrads chafing with boredom at their small college, however, those images are utopia, a heaven on Earth compared to the suffocating tedium of their surroundings. When Brit (Ashley Benson) and Candy (Vanessa Hudgens) mime oral sex to each other during an auditorium class, they stick out not for their licentious behavior but for being the only people in the room not staring blankly at personal screens that merely reflect what the giant screen at the head of the class is showing. Faith (Selena Gomez) is a church girl in a phase of awkward transition for Christian youth outreach, featuring such incongruities as a youth minister (neck tattoo, Ed Hardy-esque crucifix shirt and all) standing backlit before stained-glass windows and using the story of Christ’s sacrifice for the sins of mankind to demonstrate just how little awe the word “awesome,” a word originally intended to connote a religious feeling, has lost all of its impact. Even goody two-shoes Faith needs to get away, and spring break seems as freeing to her as it does her more raucous friends.

To a group of undergrads chafing with boredom at their small college, however, those images are utopia, a heaven on Earth compared to the suffocating tedium of their surroundings. When Brit (Ashley Benson) and Candy (Vanessa Hudgens) mime oral sex to each other during an auditorium class, they stick out not for their licentious behavior but for being the only people in the room not staring blankly at personal screens that merely reflect what the giant screen at the head of the class is showing. Faith (Selena Gomez) is a church girl in a phase of awkward transition for Christian youth outreach, featuring such incongruities as a youth minister (neck tattoo, Ed Hardy-esque crucifix shirt and all) standing backlit before stained-glass windows and using the story of Christ’s sacrifice for the sins of mankind to demonstrate just how little awe the word “awesome,” a word originally intended to connote a religious feeling, has lost all of its impact. Even goody two-shoes Faith needs to get away, and spring break seems as freeing to her as it does her more raucous friends.

Labels:

2013,

Harmony Korine,

James Franco,

Selena Gomez,

Vanessa Hudgens

Wednesday, March 27, 2013

New World (Park Hoon-jung, 2013)

Park Hoon-jung's thriller New World is too twisty by half, with so many upheavals that the plot cannot remotely support them all. Even so, it is elevated by a few dynamic setpieces, especially a late assassination attempt in a parking deck that at last matches the frame to the outlandish lurches of the narrative. Would that the rest of the film could match its heights.

My full review of the film is up at Spectrum Culture.

My full review of the film is up at Spectrum Culture.

Labels:

2013,

Spectrum Culture

Tuesday, March 26, 2013

Criminally Underrated: Miami Vice

I've written about my turn-around on Miami Vice before, a few thoughts of which are echoed in this piece for Spectrum Culture arguing it as an underrated work. That old positive review was still reluctant to use the word "masterpiece," but my love for the film has only grown in the years since I confessed the wrong-headedness of my initial pan. These days, I consider it second only to Spielberg's A.I. as the finest American film of the '00s, and I hope I make a convincing case for it.

My full article is up at Spectrum Culture.

My full article is up at Spectrum Culture.

Labels:

Colin Farrell,

Jamie Foxx,

Michael Mann,

Spectrum Culture

By The Bluest of Seas (Boris Barnet, 1936)

The following is my March entry for Blindspots.

By the Bluest of Seas begins and ends on the same images, possibly even the same shots. But the roaring waves of the Caspian Sea, and gulls taking flight against a sun bursting through clouds, emit oppositional moods at each bookend. At the start, the shots of the stirred ocean connote the sea’s unforgiving power, having destroyed a ship off-screen and whipping its surviving sailors, Yusuf (Lev Sverdlin) and Aloysha (Nikolai Kryuchkov), around like rag dolls. When they return to these churning waters at the conclusion, however, the Caspian both reflects the final release of the emotions put on forthright display in the intervening story as well as an unexpectedly warm homecoming for two men who belong on the water.

For as merciless as the sea can be, its mercurial nature can also make it warm and inviting. Once the storm calms, director Boris Barnet replaces the ominous shots of waves crashing upon each other with ones of sun-kissed surfaces glinting in the light of day, with a single wave gently rolling along like a pulse. The serenity of it relieves as much as the appearance of a boat to rescue Aloysha and Yusuf, who are taken to the nearby “Lights of the Communism” kolkhoz and gladly volunteer to help man the village’s fishing vessels. Here the film might have slipped into a censor-friendly paean to Soviet labor were the adoptive workers not instantly stricken by the sight of a woman.

By the Bluest of Seas begins and ends on the same images, possibly even the same shots. But the roaring waves of the Caspian Sea, and gulls taking flight against a sun bursting through clouds, emit oppositional moods at each bookend. At the start, the shots of the stirred ocean connote the sea’s unforgiving power, having destroyed a ship off-screen and whipping its surviving sailors, Yusuf (Lev Sverdlin) and Aloysha (Nikolai Kryuchkov), around like rag dolls. When they return to these churning waters at the conclusion, however, the Caspian both reflects the final release of the emotions put on forthright display in the intervening story as well as an unexpectedly warm homecoming for two men who belong on the water.

For as merciless as the sea can be, its mercurial nature can also make it warm and inviting. Once the storm calms, director Boris Barnet replaces the ominous shots of waves crashing upon each other with ones of sun-kissed surfaces glinting in the light of day, with a single wave gently rolling along like a pulse. The serenity of it relieves as much as the appearance of a boat to rescue Aloysha and Yusuf, who are taken to the nearby “Lights of the Communism” kolkhoz and gladly volunteer to help man the village’s fishing vessels. Here the film might have slipped into a censor-friendly paean to Soviet labor were the adoptive workers not instantly stricken by the sight of a woman.

Labels:

1936,

Blind Spots,

Boris Barnet

Monday, March 25, 2013

The Romance of Astrea and Celadon (Éric Rohmer, 2007)

Éric Rohmer goes out on a blissful high, and, in his quietly unexpected way, ends with a film that retroactively sets the stage for what came before. A period piece as filtered through yet another period, The Romance of Astrea and Celadon is as witty, warm and subtly masterful as anything the director ever made. The clash of classical, modern and druidic creates a formal tension dispelled in an outlandish conclusion that arrives at traditional, heteronormative fable only after passing through Sapphic petting. So much hay is made over Rohmer's political leanings, but like the conservative artists of old (Hawks, Ford), he often taps depths of contradictions with an unforced grace that eludes nearly all liberal message filmmakers.

My full review is up now at Movie Mezzanine.

My full review is up now at Movie Mezzanine.

Labels:

2007,

Éric Rohmer,

Movie Mezzanine

Netflix Instant Picks 3/22/13—3/28/13

Belated link to Friday's Netflix picks. Two exceptional films recently added to streaming.

Labels:

Movie Mezzanine,

Netflix

Thursday, March 21, 2013

Wattstax (Mel Stuart, 1973)

Mel Stuart's Wattstax, a document of the concert that gives the film its name, is not strictly a concert movie. Instead, it often moves from the concert to the neighborhood around it, touching on racial pride and tension the place that exploded these issues outside the Deep South. The music becomes simultaneous escape from and voice of the pain and anger on display, culminating in a performance from Isaac Hayes that focuses everything into one delightfully tacky gold chain vest.

Check out my full thoughts at Movie Mezzanine.

Labels:

1973,

Documentary,

Movie Mezzanine

Netflix Instant Picks 3/15/13—3/21/13

I missed posting this last Friday and didn't rush to get it up later because two of my Netflix picks for the week were set to expire by Saturday. On the plus side, the two films I singled out as expiring last Saturday apparently got their streaming licenses renewed, because when I checked my queue during the week, both Metropolitan and Slacker were still there with their expiring soon warnings removed. Be sure to check them out.

Read my full post at Movie Mezzanine.

Read my full post at Movie Mezzanine.

Labels:

Movie Mezzanine,

Netflix

Tuesday, March 19, 2013

The Girl (David Riker, 2013)

In some ways, I think I might resent the modern indie vanguard of message movies over the classic Kramer model. At least the usual sort has the decency to be shameless in its hectoring tone, while these smaller pictures try to sneak their laborious moralizing under cloaks of false ambiguity. It is agonizing to see Abbie Cornish wasted yet again in a part predefined by visualizations of the character bio in the script, given no chance to build a human out of her character. Likewise, the redemptive arc David Riker ties into a muted cry at our broken and cruel immigration system serves primarily to exonerate the white woman from her guilt. The only thing worse than awards-baiting studio productions about serious issues are films like this that commit the same sins but think themselves superior to their larger-scaled counterparts.

My full review is up now at Spectrum Culture.

My full review is up now at Spectrum Culture.

Labels:

2013,

Abbie Cornish

Saturday, March 16, 2013

The Girl Can't Help It (Frank Tashlin, 1956)

The three Tashlin films I've seen thus far have all been exemplary displays of comedy, their feverish blend of intricate aesthetic craftsmanship and rapid-fire farce a tremendous live-action application of the director's animation background. If The Girl Can't Help It lacks the same level of total perfectionism as Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, that is only because even Tashlin cannot bring the rawness of the emerging rock scene fully under his satiric control. In its own way, that makes this even more exciting, as no other film has ever so perfectly captured the depth of social upheaval rock 'n roll brought to the kind of society Tashlin plays up as stagnant around explosive acts like Fats Domino and Little Richard. In a particularly amusing twist, gangsters past their prime find new vigor in the rock scene, but it is the music, not their criminal pasts, that bring back their menace.

Check out my full article on the film over at Movie Mezzanine.

Check out my full article on the film over at Movie Mezzanine.

Labels:

1956,

Frank Tashlin,

Jayne Mansfield

The We and the I (Michel Gondry, 2013)

There is so much promise in Michel Gondry's mostly laissez-faire bus ride with Bronx kids antsy to start their summer break that its failure to meet its subtly established goals is all the more regrettable. At times, The We and the I creeps toward the kind of ethnographic view of people who attain universal import in their strict localization and demographic layout that has served Richard Linklater so well. But where Linklater slowly draws human beings, and then a world, from types, Gondry cannot handle the density of his confined population and can only begin to deepen characters after he dumps most of them from the film. The ones who stay are sketched in strokes too broad for what can otherwise feel so real. I've seen this get mostly positive notices, but I could not help but be disappointed.

My full review is up now at Spectrum Culture.

My full review is up now at Spectrum Culture.

Labels:

2013,

Michel Gondry

Friday, March 8, 2013

Netflix Instant Picks 3/8/13—3/14/13

Slim pickings this week in terms of notable additions and deletions from Netflix, but at least it's balanced out with one of Howard Hawks' finest films. A good Hawks is worth its weight in gold.

Check out Corey's and my picks over at Movie Mezzanine.

Check out Corey's and my picks over at Movie Mezzanine.

Labels:

Movie Mezzanine,

Netflix

Thursday, March 7, 2013

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (Jacques Demy, 1964)

The following is my belated February entry for Blindspots.

Jacques Demy announces the “movie”-ness of The Umbrellas of Cherbourg from its opening iris shot, a silent-era throwback that begins the film with an effervescent charm. That carries through to the credits, played when the camera tilts from its view to a shot looking straight down as people walk by carrying umbrellas. Demy further stresses the artificiality: as the credits roll, people walking under red umbrellas move across the screen one at a time in seemingly random directions (but always perpendicular to one side of the frame). Then, when the title credit flashes, Demy changes up the color-coordinated but distinct individuals with the sudden appearance of a row of people holding umbrellas of different colors. The spontaneity of movement and uniformity of color inverts, but neither arrangement is any more real than the other.

Demy plays up the immaculate, cinematic construction of the musical throughout the film, casting Cherbourg in outlandish pastel palettes of purples and greens and converting all dialogue to song. (In another bit of directorial control, Demy overdubs his actors with professional singers.) Yet for all its bright color tones and the swing of Michel Legrand’s brassy score, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg tells a decidedly downbeat story, one flecked with an honest appraisal of social constraints placed on people personally, financially and politically. Where similarly bitter subject matter for musicals has been communicated through excessively revisionist cruelty (Dancer in the Dark) or styleless vacuity (Les Misérables), Demy maintains all the elements common to the genre and, more impressively, keeps them all in sync.

Jacques Demy announces the “movie”-ness of The Umbrellas of Cherbourg from its opening iris shot, a silent-era throwback that begins the film with an effervescent charm. That carries through to the credits, played when the camera tilts from its view to a shot looking straight down as people walk by carrying umbrellas. Demy further stresses the artificiality: as the credits roll, people walking under red umbrellas move across the screen one at a time in seemingly random directions (but always perpendicular to one side of the frame). Then, when the title credit flashes, Demy changes up the color-coordinated but distinct individuals with the sudden appearance of a row of people holding umbrellas of different colors. The spontaneity of movement and uniformity of color inverts, but neither arrangement is any more real than the other.

Demy plays up the immaculate, cinematic construction of the musical throughout the film, casting Cherbourg in outlandish pastel palettes of purples and greens and converting all dialogue to song. (In another bit of directorial control, Demy overdubs his actors with professional singers.) Yet for all its bright color tones and the swing of Michel Legrand’s brassy score, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg tells a decidedly downbeat story, one flecked with an honest appraisal of social constraints placed on people personally, financially and politically. Where similarly bitter subject matter for musicals has been communicated through excessively revisionist cruelty (Dancer in the Dark) or styleless vacuity (Les Misérables), Demy maintains all the elements common to the genre and, more impressively, keeps them all in sync.

Labels:

Catherine Deneuve,

Jacques Demy

Wednesday, March 6, 2013

Written By (Wai Ka-fai, 2009)

Better known as Johnnie To's creative partner and co-founder of To's independent Hong Kong company Milkyway Image, Wai Ka-fai is also one of the most distinctive screenwriters in contemporary cinema. His collaborations with Johnnie To are tinged with the supernatural and the metaphysical, making for scripts packed with cyclical, mirroring movements perfect for To's imagistic direction. Written By, directed solely by Wai, operates with one of his densest screenplays, co-written with Au Kin-yee. Its recursive movement of characters shaping and reshaping each other's fates through fantasy leads to Kaufmanesque blurring of dimensional boundaries, but where Kaufman's work plays on intellectual lines, Wai's endless loops serve to bring his story's immense grief closer and closer to the surface where the characters, and audience, can truly confront it.

Labels:

2009,

Kelly Lin,

Lau Ching-wan,

Wai Ka-fai

Tuesday, March 5, 2013

Something Old, Something New: Floating Clouds/Tabu

When I recently caught up with Mikio Naruse's Floating Clouds, I was struck not only by its considerable power but in how strongly it reminded me of a similarly structured paean to lost empires, Miguel Gomes' Tabu. Naruse's burns with the white-hot intensity of a nation still so close to its loss of status that it has not even come to terms with what was lost (or how to separate that sense of loss from what has already been idealized). Gomes' film is more analytical, using its own flashbacks to criticize the falsity of romanticized imperialism through more political contrasts. Both are great films, though Naruse's proves superior for burying its own sense of irony underneath genuine, raw humanism. Though Tabu plays in reverse, save it for the B-movie for a pick-me-up from Naruse's devastating finale.

My full piece is up now at Movie Mezzanine.

My full piece is up now at Movie Mezzanine.

Monday, March 4, 2013

The Band Wagon (Vincente Minnelli, 1953)

As a belated celebration of Vincente Minnelli's 110th birthday, I wrote some brief thoughts on his excellent Astaire vehicle and cinematic masterclass The Band Wagon for Movie Mezzanine. I was also spurred on by a brief, friendly debate on Twitter (referenced in the piece) over whether this film was superior to Singin' in the Rain, and I slightly frame my article around the contrast between the two. Outside the silly preferential debates, this is a great film, and like An American in Paris, blatantly theatrical in a way that shows the limitless of cinema.

My full piece is up now at Movie Mezzanine.

My full piece is up now at Movie Mezzanine.

Labels:

1953,

Vincente Minnelli

Saturday, March 2, 2013

Netflix Instant Picks 3/1/13–3/7/13

Another Friday, another list of Netflix Instant titles to watch from myself and Corey Atad. A lot expired in the wee hours of the morning, but US viewers did at least gain one wonderful genre picture from a great director as a trade-off, as you'll see in the post. Corey's got some great stuff too, from Carol Reed to one of my favorite films of the last few years.

Check out our full post at Movie Mezzanine.

Check out our full post at Movie Mezzanine.

Friday, March 1, 2013

Oeuvre: De Palma: Body Double

Body Double is one of my favorite films, so I jumped at the chance to write about it for Spectrum Culture's running feature reviewing all of Brian De Palma's films. (I highly recommend reading all of the other pieces, by the way; a lot of great stuff from some terrific writers.) I've written about the film before and make some of the same observations, but I continue to be struck by its sense of anarchy, its nihilistic rejection of the same studio system to which De Palma pays so much tribute. As I argue in my article, it is the quintessential De Palma film, pitched perfectly between Godardian satire and Hollywood gloss, as much the target of its own commentary as the vehicle for scathing condemnation of everything around it. A masterpiece.

My full piece is up now at Spectrum Culture.

My full piece is up now at Spectrum Culture.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)